Ancient

Indian Walls

By

Captain William N. Page

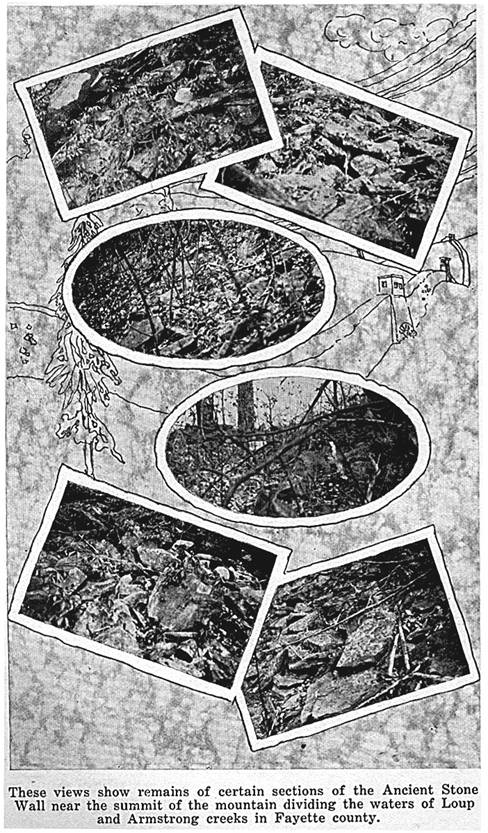

"Near

the summit of the mountain dividing the waters of Loup and Armstrong

creeks, in Fayette county, West Virginia, there is found the remains

of a very remarkable stone wall, which was well known by the first

white settlers in the Kanawha valley, and to the Ohio Indians who passed

along this route in hunting and other expeditions, toward the valley

of Virginia, where, according to their legends, the buffalo migrated

periodically from the Ohio valley, and further west.

The

late Dr. Buster, who was among the first white residents of the Kanawha

valley, resided at the foot of this mountain, on the south bank of

the river, during a long and active life. No white man had ever occupied

the ground upon which his father built his cabin, according to record;

and history of the paleface here, is absolutely complete within this

family. Paddy Huddleston, probably the first white settler within

the limits of Fayette county, lived just up and across the river, practically

in sight; and from his house Daniel Boone trapped beaver. In my

last interview, about 1877, though a very old man, his mind and body

were still active and vigorous. He remembered talking to the Indian

'medicine men' in his boyhood, as they frequently passed up the river,

and discussed this wall with the numerous relics of bones, stone implements

and pottery found all over the surrounding bottom lands. According

to his statements the Indians knew of these monuments, but claimed no

part in them. One of their legends sets forth the fact that the

Kanawha valley had been occupied by a fierce race of white warriors,

who successfully resisted the approach

of the 'red man' from the west for a long time, but had finally succumbed,

and passed away in death. The Indians claimed never to have occupied

the valley, except for hunting expeditions; that they found these relics

old when they first entered; and that their origin was beyond their records.

Though

such legends are not always reliable, a careful study of the conditions,

habits of the people, and the bones found at the foot of the mountain,

inevitably leads to more than the suspicion of a prehistoric race,

differing from the North American Indian in physiognomy, character

and habits.

Loup

and Armstrong creeks empty into the Kanawha from the south, and are

nearly parallel - three miles apart - for a distance of about ten miles. Like

the river, both creeks have cut deep gorges through the nearly horizontal

carboniferous strata, and the smaller tributaries, heading against

the 'divide,' have also cut out to the creek level at the points of

junction. The result of this denudation is a mountain, rising

1,500 feet above water level, with ribs, holding their altitude well

toward the creek, while the main backbone, or watershed, has alternate

knolls and low gaps, with a difference of about 300 feet elevation

between the high and low points. As the hard sandstone or of

the 'conglomerate series' are under water level here, the softer, overlaying

strata of the 'lower barren measures' have been weathered so that the

slopes are comparatively smooth.

The

wall in question has been constructed along the approximate contour

of the mountain, about 300 feet below the high summits and just under

the low gaps, conforming as nearly as possible to such contour, it

winds around each rib, or spur, until a low place is found through

which to pass, when it finally crosses the main ridge and returning

in the same manner on the other slope, makes a complete enclosure facing

the river, of about three miles in length and varying in width from

a hundred yards to a mile, or more.

The

total length of this wall has never been measured, but can hardly be

less than eight or ten miles. A single cross wall at a narrow

point divides the enclosure into two nearly equal arms, in one of which

there is an unfailing water supply of more than a half cubic inch of

flow, from a coal measure which has been cut by a low gap at this point. When

I first saw this spring in 1877, the existence of this coal measure

was unknown, and the old hunters of

the neighborhood were under the impression that the water came from

a well, sunk upon the watershed of this gap and filled up by leaves

and time. It was a circular pool about six feet in diameter,

and three or four feet below the surface. Dr. Buster stated that

it was at least ten feet deep when he first saw it, and held to the

opinion of a well; but I am satisfied now that it is only the drainage

from the coal seam mentioned, upon a floor of impervious clay. It

is located on the dip side of the coal escarpment, which by actual

survey covers an area of thirty-seven acres, with a maximum covering

of about 200 feet. The hole has probably been scooped out by

bear and other wild animals, as marks upon the neighboring trees from

bear claws is evidence that this has been, as is yet to some extent,

a favorite wallow, in which they roll like swine, and in their gambols

they claw the bark of trees so as to leave the marks as long as the

tree may stand.

Near

this spring, however, and within the partition farthest from the river,

there has been recently found two large circular heaps of stone, indicative

of some kind of tower structure; and it is more than probable that

their location had reference to the water supply, which is not found

elsewhere within the structure. These circles were about twenty

feet in diameter, and their present appearance indicates an original

height of about twenty feet.

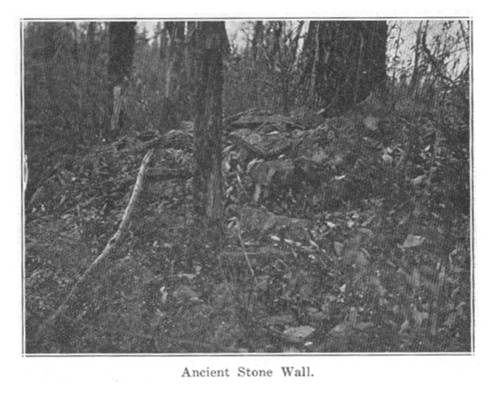

The

wall itself has been constructed of loose stone, without any kind of

cement, and of such dimensions as could be readily handled, without any

attempt at quarrying or facing. Along the steepest slopes it has

fallen and can be traced only by the bench of debris, but in some places

where it crosses the ridges, and has level foundations, some idea of

the original dimensions may be had. It is safe to estimate a height

of six feet, upon a foundation width of from six to eight feet. Nearly

all the loose stone within the enclosure seems to have been carried out

for use in the structure; but in many instances blocks of 'black flint

ledge' may be observed in the wall, and since the outcrop of this ledge

is lower down the slope, it is certain that such stone had been carried

up hill. This fact alone is evidence of human labor; but no one

can follow the traces far without ample proof of some crude architect. Though

at an altitude of two thousand feet above tide, huge trees abound, many

exceeding five feet in diameter, with hundreds of years growth. At

points may be seen oaks four feet through, evidently sprouted since the

foundation of this wall was laid, as the stones have been lifted and

misplaced by their growth. Wherever a cliff has been encountered,

it has been utilized as far as possible, and as a rule the wall has been

joined to such cliff at the foot, rather than at the top. This

would indicate an object to guard against entrance from without rather

than to prevent escape from within, as in some instances the cliffs have

sufficient slope to enable ordinary animals to descend, but are too steep

to climb. The wall has been built with so much batter and so roughly

that it could never have been intended for any kind of fortification,

nor to confine, nor to keep out, any but domestic animals.

The

flat lands along the south bank of the river, between the mouths of

these creeks, and immediately in front of that portion of the wall

facing the Kanawha, varies in width from five hundred to two thousand

feet wide, while the bottoms on the opposite side are very much more

extensive and better suited for agricultural purposes; yet the greater

portion of the bones and relics are found on the south or wall side. About

two hundred acres of this bottom land, near the mouth of Armstrong,

is literally filled with bones and implements of some human race, whose

history has been buried with their dead.

Four

years ago, in the construction of a railway, it has become necessary

to cut through a part of this ground, near where the old Buster cabin

had stood. This cut was about two hundred feet long, thirty feet

wide, and with a maximum depth of ten feet. Within a distance

of one hundred feet there were uncovered about thirty skeletons, all

buried in a like position, at an average of four feet. There

was no evidence of mound, or monument of any kind except a few loose

stones piled upon each set of bones, below the surface, and there was

no indication to point to this particular spot, which was near the

river's bank. Without exception the bodies had faced the east,

or rising sun, in a horizontal position from the hips down, and reclining

at an angle of about thirty degrees from the waist up. The bones

were in a fair state of preservation, but many crumbled with the hand. The

soil being a sandy loam, had filled every crevice and marrow duct,

so that even the skulls were crushed with the weight of handling and

it was with much difficulty that anything was preserved.

I

measured several skeletons in position and found them to average about

five feet, ten inches. With one exception, the cranium was well

proportioned, with broad and prominent forehead, and facial bones more

nearly resembled the white, than the red race. This exception

was in all probability, a deformity, else it was a very much lower

order of animal intellectually, though not physically. The teeth

indicated an age of about twenty-five, and imbedded in the front of

the lower jaw bone was a fully developed tooth which had never penetrated

the bone. The skull was canoe shaped, sharp front and back, long

and very narrow. The occipital bone was out of all proportion,

curved under, and terminating in a sharp point. The parietal

bones occupied nearly the entire skull area, as the coronal and lambdoidal

sutures were so far forward and back of the usual position that both

the frontal and occipital bones were curiosities. The frontal

bone was also pointed, and there was no break in the canoe curve from

the eye to the nape of the neck. Other bones denoted full and

complete development; but he must have been a fearful sight in life.

Along

with these bones were found those of many food animals, such as bear,

deer, elk, &c., birds and fish scales. About three feet below

the surface, a regular stratum of phosphate, about eight inches thick,

extended over the greater area of the cut. Upon close examination,

enough fish boned and scales remained to indicate its origin. In

places bits of charcoal, slag from melted sand, and pieces of charred

bone showed that they feasted on cooked meats. The implements found

were all stone, pottery and bone. The stone instruments consisted

of greenstone celts, precisely the same as those of the Continental stone

age, scrapers for dressing hides, flint spear and arrow heads in great

abundance in various sizes and shapes, and a lot of quoit-shaped stones,

which had been marked and evidently used in some system of weights, as

many are exact multiplies of others. The arrow heads were nearly

all of the war variety, made to be left in the wound, but not notched

fro a thong fastening, as was customary among Indians with their points

for game. Some of these points were the sharpest and slenderest

specimens of flint workmanship I have ever seen; they were no more than

two inches long

and less than half an inch at the shaft end, or widest part, tapered

to such a fine point that they could be used comfortably as pin to prick

splinters out of the hand. One, in particular, had three sharp,

equal points, which at the shaft end (for which it was notched), made

a cross, or four pointed star. The spear heads were unusually

sharp and made for business, as was the case with the edges of the celts. The

pottery, like that found in the valley, was made from the river mussel-shells,

coarsely pounded and mixed with loam. A great variety was found,

some of the pieces were large enough and nearly perfect, showing the

effects of use, and heat over a fire. The bone implements consisted

mainly of long needles, awls, etc., for the manufacture of skins. The

eye of the needle was notched to receive the thong, on the same principle

as ours today. Those which had been polished were as sharp and

sound as when made from the small rib of a deer; but the unpolished portions

of the awl had crumbled off. In the same line of bone there was

also found 'wampum' made from very small segments of the spine of some

fish or reptile; and the value of each piece seemed to depend upon the

amount of labor which had been bestowed upon it. There were no

holes through these beads, nor arrangements for stringing them together,

consequently they could not have been intended for any kind of ornament. They

varied in size from a No. 8 to a No. 2 shot, but each had been carefully

polished. Imbedded in the sand, in the mouth of one of the skulls

were found two pieces of thinly beaten copper, nearly three inches long,

and rolled as if around an arrow shaft; they had probably been one, but

broken in two. This was the only metal found; and only one steatite

pipe, with the stem very accurately bored and split in halves. The

nearest steatite in position lies east of the Blue Ridge, in Virginia,

and neither this nor greenstone is found in the river silt.

The

first question is: Who built this wall, when, and for what purpose? It

may be safely assumed that it antedates any historic records or legends

in our possession. The Indians found here knew of its existence,

but nothing of its origin or purpose; and as far as we know they were

not a race to undertake manual labor. The theory among old hunters,

that it was a game pen, is refuted early in examination, since nothing

but a domestic animal could be fenced by such a structure. That

it could have been intended for any

kind of agricultural purpose seems equally as improbable for the same

reasons, and for the further reason that the location is practically

inaccessible, while the valleys below were broad and fertile. In

portions of the enclosure there is a deep, rich soil; but a large part

of it is barren, rocky crest, which would certainly have been left

out where the same labor might have been employed. There remains

the question of fortification, which seems equally as improbable, except

so far as it might have afforded immediate protection in actual fight;

but with the weapons probably in use, a tree would have answered the

purpose better. Though the towers may have a war-like sound, as

a matter of fact they were in a position where they would have been of

the least service in defending the wall against an outside attack, though

they might have served to defend the water supply.

It

seems to me that we must look for some other object and conditions,

entirely foreign to any Indian custom; and that not only the bones

at the foot of the mountain, but the archaeological history of the

entire Kanawha valley furnishes a clue. That the Kanawha valley has been densely

populated by some prehistoric race, differing from the Indian in intelligence,

manners and customs, there can be little doubt. The soil everywhere

bears indisputable evidence of their numbers and handiwork, beside which

the hundred years of white occupancy and monuments would sink into insignificance

with a like test of time. From Kanawha Falls to Charleston, a distance

of forty miles, scarcely a post hole can be dug without disclosing some

evidence of this people. It has been asserted that the Aztecs,

or some Arian race from Mexico, had followed up the Mississippi and Ohio

to the Kanawha, and the numerous mounds found in this valley has been

cited as one evidence. Such a theory is plausible as the route

is a natural highway, followed later by the Spaniards and French without

much loss of time. It is also natural to presume that a southern

race would have settled in greater numbers along the Kanawha, than in

the upper Ohio valleys. But the question is, whether the bones

found at the mouth of Armstrong creek, without sign or monument, belong

to such a race, or to the North American Indian? The physiological

features are clearly against the latter assumption; and that they were Sun

Worshippers is demonstrated by the sameness in

position of all bodies found. The quantities of fish and bones

of wild animals, prove that they were an active race of meat eaters,

and that they cooked their food in vessels of clay; and that they were

bold is certain from the large portion of bear tusks, some of which were

enormous, and must have been ugly customers to tackle with stone weapons. If

we connect these bones with the stone wall in question, it seems to me

that it can be more readily accounted for in some Essenic religious

rite. The elevation of the mountain is such that the sun can

be seen much longer than from the valley, and the position of the towers

were favorable to such observation; and being near the center, they were

doubtless sanctum sanctorum of the enclosures, and the abode

of some high priest. It is more than probable that some kind of

serfdom or slavery existed, whose surplus labor was directed to such

monuments, probably not so much for record, as for occupation or punishment,

as the wampum shows that they placed some value on labor.

A

comparison of ages between the wall and bones would certainly not place

the latter ahead of the former, though the reverse might be the result;

but it must be borne in mind that under certain conditions the decomposition

of bone is no index to age or time, as it is pretty well authenticated

that a period of two thousand years has failed to obliterate the human

skeleton, probably as much subject to oxidation as there have been. I

am perfectly certain that the Armstrong bones are very ancient, but

I am not competent to approximate any definite time.

I

have heard of a similar wall on one of the Paint creek mountains, ten

miles down the river, but have never seen it. As none of our

race ever occupied these mountain tops and they have been rarely visited

except by huntsmen, other evidence might easily have been overlooked;

and since we have no records more ancient in connection with the human

race, it is hoped that the subject will receive more attention in the

future than in the past."

The

following lines were written by Captain William N. Page, and express

his conviction as to the antiquity of the relics mentioned in the foregoing

article:

"Entomb'd

for ages, facts and fancies, here have risen

From prehistoric records. Breaking nature's

prison -

By steps as slow as forest growth, canyon deep,

Cut through everlasting rock; with slopes too steep

To climb with naked feet. Nor can the truth

be caught

When fact is wing'd by fancy in the flight of thought.

Kanawha's floods have buried race and name,

By countless thousands, still unknown to fame.

But written records in the sands, along its winding

shore,

Is record older than the tombs of Egypt's lore." |

The

Smithsonian Institute had an investigation by Col. P. W. Norris of

the wall and of the ancient burial ground so graphically described

by Captain Page. Volume 12, Bureau of American Ethnology Report,

pages 412 to 434, contains a paper by Dr. Cyrus Thomas, which embodies

the report of Col. P. W. Norris, who died in 1885, while engaged in

explorations in the Kanawha valley. The death of Col. Norris

ended the investigation, and comparatively few of the younger generation

in the county know of the existence of the wall.

Some

years ago, a company mine the coal from under the mountain on which

this ancient wall is found. The coal seam was nearly on a level

with a part of this stone wall. One of the miners related that

when they had reached a point nearly under the center of this knoll,

they found the coal gone from under same over an area of about one

fourth of an acre, and that they failed to find any entrance to this

excavated place. It was also stated that within said excavated

place they found several small cone-shaped mounds about two feet high

which were formed of sand, which evidently had, in centuries past,

dripped from the sandstone top and finally formed these cone shaped

piles of sand, which in the lapse of time had become petrified.

The

mysteries surrounding these antiquated walls certainly provide a very

wide and interesting field for investigation.

A

recent visit by the writers of this history finds the wall but little,

if any, changed since the visit of Captain Page about fifty years ago. Two

things, however, they did discover - one, a great stone in the center

of the enclosure which was probably the throne of the chieftain of

the race or the sacrificial alter of the strange people whose beginnings

and end are lost in the mists of antiquity. The other disclosure

was that the tower on the outside of the wall apparently covers the

entrance to a cave, and the supposition is that the tower on the inside

serves a like purpose. Were these people, then, cave dwellers? To

what depth does the ancient passage way beneath the stones lead? What

would one find therein? These questions we leave for the more

intrepid to answer.

To

show that the entire Great Kanawha river valley, heading in Fayette

county, was the scene of early operations of ancient and distinct races,

we give a few notes concerning finds of the life and activities of

prehistoric people:

Ten miles below the mouth of

Armstrong creek, on the Kanawha river, is another wall similar to the

one in Fayette county described by Captain Wm. N. Page. It is on

a high mountain, facing the river, just above the mouth of Paint creek. The

characteristics of the two works are so nearly alike that the foregoing

description of the one at Loup creek renders unnecessary any description

of the one at Paint

creek, except to say that it is erected on a smaller scale.

At

the base of the Paint creek mountain, too, is an extensive burying

ground, similar to the one described. It is just where the village

of Pratt (formerly Clifton), now stands; and so numerous are the remains

that excavations for any purpose are almost sure to unearth skeletons,

as well as stone, bone, earthenware, copper implements, and relics.

Within

the village of Brownstown, ten miles above Charleston and just below

the mouth of Lens creek, is another such burying ground. Some

time ago two skeletons were found together here, one a huge frame about

seven feet in length and the other that of a deformed dwarf about four

feet in length.

Graves

at any of these places are not marked with mounds or any surface indications. The

probability naturally suggests itself that those buried there, and

who built these stone enclosures were a different race from the

Mound Builders.

Some

young men, while hunting on the mountain near Cannelton discovered

what seemed to be the walled up entrance to a cave in the face of a

cliff. Impelled by curiosity, they pried out the stones and effected

an entrance to a cavity, where they found the remains of human animal

bones, flint implements, a piece of coarse woven fabric, and some dried

berries. The berries were in flat layers between a course of

small twigs or stems below, and another course above. This is

the only instance, so far as we know, of a cave burial in the valley.

There

have been no recent examination and explorations of these ancient works

here in the Kanawha valley, except as aforementioned, and the hundreds

of ancient earth and stone works offer a rich field of study of the

ethnologist and archaeologist.

The

History Of Fayette County, West Virginia. This

book was written by J. T. Peters and H. B. Carden. It

was published in 1926 by the Fayette County Historical Society,

Inc., Fayetteville, West Virginia, and printed by Jarrett Printing

Company, Charleston, West Virginia.

CIVIL

WAR ~ PRINTS & GRAPHICS ~ BOOK

PUBLISHING ~ STORE

![]()